Adam Shatz, Franz Fanon, Palestine

You probably first heard Adam Shatz’s name on Twitter, where people were annoyed at an article that was published in the London Review of Books, in which he leveraged the work of the Martiniquan psychoanalyst, theorist and revolutionary Franz Fanon into a critique of Hamas’ Al-Aqsa flood operation of 7 October 2023, which hinged on a distinction between ‘violence as a cleansing force’ as opposed to ‘violence as a disintoxicating force’. [my emphasis]. In a footnote in Shatz’s recently-published book on Fanon, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Life of Franz Fanon, Shatz writes the following:

The English translation of la violence désintoxique as “violence is a cleansing force” is somewhat misleading, suggesting an almost redemptive elimination of impurities, whereas Fanon’s more clinical word choice indicates the overcoming of a state of drunkenness, the stupor induced by colonial subjugation.

I am of course open to being corrected by someone with better French than me, but this is a distinction that seems to me to be largely literary. Whatever we might think of anti-colonial resistance, the subjective palatability of violence as a tactic within it, Fanon’s commitment to praxis up to and including it is beyond dispute. This is clearly evident even to Shatz, as he himself writes:

Fanon understood not only the strategic necessity of violence but also its psychological necessity. And he understood this because he was both a psychiatrist and a colonized Black man.

A significant part of the reason Shatz’s critique did not land with many people, does not land with me, is a question of overtones, of subtext, a difficulty that this article is to a large extent concerned with. It was entitled ‘Vengeful Pathologies’ — this may not have been his choice — and sits within a tradition of expressions of discomfort coming from a left / liberal-left intelligentsia with the actions of anti-imperialist organisations, particularly those which are not necessarily secular and receive support from nation states which aren’t either. It can be hard to know what to do with the hollow sound critiques separate, not just from an alternative vehicle for liberation, but even from a vision towards an alternative. The development of two-nation institutions, boycotts, non-violent resistance, marches, strikes, mass movements, campaigns, all of these have been tried, and are ongoing, but none of these have yet managed to stop the killing. If we are all not yet well-informed, we are in a position to investigate the history of anti-imperialist and of socialist struggle, in which it is clear that revolt against exploitation is undertaken by diverse factions with distinct strategies which prevail over others at different times.

On the 76th anniversary of the Nakba, the mass expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homes, their land, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics released a report which said that 134,000 Palestinians and Arabs had been killed by the forces of the Zionist state both in and outside Israel in the decades since. This is roughly four times the number of casualties and deaths sustained by both Israeli civilians and military forces. This is frankly a one-sided massacre waged by one of the most well-equipped military states in world history and wrangling over what form of resistance is adequate seems hopelessly, hopelessly beside the point.

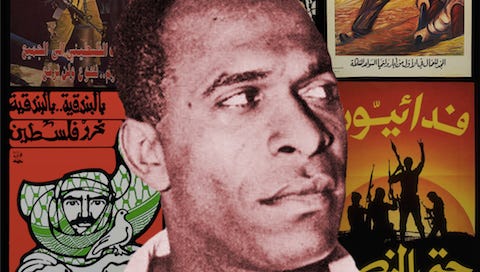

I was surprised then, to find much that was worthwhile in Shatz’s biography of Fanon. Shatz positions his life and work within multiple fields: Martiniquan cultural nationalism, French Republicanism, existentialism, anti-psychiatry and cultural studies. Freud, Lacan, Sartre, Stuart Hall collectively loom as large as the FLN. In this sense it is a welcome rectification in the English-language press; a footnote in the edition I have of The Wretched of the Earth rebukes Fanon for his shoddy scholarship. Shatz offers significant insights into his working methods and his personal life and a hugely useful overview of the early years of an anti-colonial international: the Bandung Conference, the Tricontinental, the non-aligned movement. The effect here is inspiring but also depressing. We have gone a long way from Che Guevara’s later injunction for two, three, many Vietnams, a self-conscious attempt to expand the hot frontiers of anti-imperialism to undo the centuries of plunder, enslavement and underdevelopment forced on the majority of the world’s population. Fanon and his closest comrades within the FLN were committed to this vision, which encompassed pan-Africanism and pan-Arabism; decisive fractions of a comprador bourgeoisie taking more pragmatic stances relative to the American empire were not.

Complications arise when Shatz considers the actual application of Fanon’s thought. There is no smoking gun here as such. Shatz is a good writer. His tone fits a New Left Review / London Review of Books house style, the strengths of which are significant. Dispassionate, thoughtful, they are generally readable, but also flexible, allowing even for the expression of wry humour or even explosive indignation every once in a while. The author’s capacity to encompass often vast amounts of primary and secondary evidence engenders a sense of being above the ruck and this elevation of sophistication as I have written elsewhere facilitates some refraction of evidence towards reactionary ends. Below I provide a series of block quotes from Rebel’s Clinic:

The Wretched of the Earth was required reading for revolutionaries in the national liberation movements of the 1960s and ’70s. It was translated widely and cited worshipfully by the Black Panthers, the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa, Latin American guerrillas, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the Islamic revolutionaries of Iran. From the perspective of his readers in national liberation movements, Fanon understood…the strategic necessity of violence

[…]

Some readers in the West have expressed horror at Fanon’s defense of violence, accusing him of being an apologist for terrorism—and there is much to contest. Yet Fanon’s writings on the subject are easily misunderstood or caricatured

[…]

Fanon came to believe that reform was not just inadequate but also a lie—that, short of a revolutionary transformation, he would be complicit as a practicing psychiatrist in the culture of confinement that sequestered Algerian bodies and souls. He was not wrong. But the political choices he made in the world outside the hospital were more troubled, and sometimes required a denial of the “man who questions”—a tactical surrender of freedom that did not escape his notice or leave him without regrets.

[…]

that experience generated nearly as many illusions as illuminations. I admire Fanon—his intellectual audacity, his physical bravery, his penetrating insights about power and resistance, and, above all, his unswerving commitment to a social order rooted in dignity, justice, and mutual recognition—but, as you will see, my admiration for him is not unconditional, and his memory is not well served by sanctification.

In this book, I will be exploring the questions that Fanon asked, and the questions he failed to ask, because both explain so much, not about the prophet but about the man. Fanon once said that all he wanted was to be regarded as a man. Not a Black man. Not a man who “happened” to be Black but who could pass for white. Not an honorary white. He had been all those men, in the eyes of others, but never just a man. He wasn’t asking for much, but he might as well have been asking for the world—a different world.

Taking these quotes together one can see that Shatz’s Fanon is at his most vital, not as an activist, which requires the sundering of the critical intellect to a cause, an organisation, an armed movement that requires its adherents to balance their subjective independence as an end in itself. Fanon’s work is best as an expression of the ambivalent pessimism of human experience, a negative existentialism, who rather than grappling with the situation as it is wants ‘a different world’. None of this is untrue, strictly speaking. Human beings are complicated, contradictory, intellectuals who authentically commit themselves to the transformation of social life perhaps even more so, caught as they are between the utopian vision and day to day life that requires compromise and tactical retreats, but what is at work here for Shatz is a subtle antimony between thought and action. t

Turning now to his rendering of Albert Camus and Richard Wright I see a form of admiration that is less equivocal at work:

Camus decided to hold his tongue in public. But he began to spend even more time in Algiers, visiting his aging mother. Some of his Algerian friends avoided him, but others understood his reasons for not supporting the rebellion, even if they regretted his position.

[…]

In the last two years of his life, Camus confined his thoughts on Algeria to his journals, where he confessed that his love for his mother country was so fierce that it had led him to betray the principles he had espoused throughout his life. “It is myself that for nearly five years I have been criticizing, what I believed, what I lived,” he wrote. “This is why those who shared the same ideas … are so angry with me; but no, I’m making war on myself, and I’ll destroy myself or I’ll be reborn.” In the journals, he turns decisively against “the moral point of view”—the view he had taken for decades—concluding that it is “the mother of fanaticism and blindness.” He is clear about the price he has paid for abandoning it, the loss not only of the moral prestige he had earned in the Resistance but of a coherent moral outlook: “Now I wander among the debris, I am lawless, torn apart, alone and willing to be, resigned to my singularity and my infirmities. And I must reconstruct a truth, having lived my whole life in a kind of lie.”

But on December 11, 1960, two days into de Gaulle’s visit, in all the major cities, Algerians—men, women, children, the elderly—poured into the streets en masse to demand independence, waving the banned flag of the FLN and carrying banners reading “Muslim Algeria!” and “Negotiate with the FLN!” They clashed with police and European ultras, and converged on European neighborhoods. In Belcourt, a poor section of Algiers where Camus’s mother lived, more than ten thousand Algerians occupied the streets.

Richard Wright:

Wright had left behind the angry didacticism that Fanon had admired in his early fiction in favor of an inquisitive and probing literary journalism that questioned many orthodoxies, including those of the anti-colonial left. While Wright welcomed the fact that Africans and Asians were now able to express their “racial feelings … in all their turgid passion,” he could not bring himself to embrace Third World nationalism; at Bandung he had been troubled by the growing power of race and faith, the superstitions with which he’d wrestled back in America. “My position is a split one. I’m black. I’m a man of the West … I see and understand the West; but I also see and understand the non- or anti-Western point of view. How is this possible? The double vision of mine stems from my being a product of Western civilization and from my racial identity.” That “double vision” was not simply a form of torment, as Du Bois had described “double consciousness.” It was an intellectual asset, he believed, allowing him to “see both worlds from another and third point of view,” and to see the colonized as both “victims of their own religious projections and victims of Western imperialism.”

In fact, it had taught him a great deal: while Wright’s sympathies lay with the colonized, he understood—thanks to his own experiences as a Black refugee from the South who had made his way north in the Great Migration—that the road to freedom was mined with obstacles, both economic and psychological. The very nature of imperialism, including the Western education and secular styles of thought and ideology it had exported to the colonies, had created forms of dislocation that political independence would not instantly overcome. In retrospect, Wright’s assessment of the postcolonial condition was full of suggestive ambiguities, unsparing in its indictment of the West but also alert to the allure of nativism and other sectarian passions—a problem that Fanon himself would soon be forced to address.

We can perhaps see the reason pernicious fraud Zadie Smith blurbed this book.

The idea that the autonomous intellectual, who takes the more complicated path, the more difficult one is a theme, but one that is never directly addressed, and this seems to me to be a failure to seriously pose the question as to how freedom is to be achieved. The refusal to pose this, to take it up, is the real distortion. As Abdaljawad Omar says in an interview with Louis Allday:

This is a political sin par excellence, because if anything Palestinian resistance operates on a highly tangled architecture of emotions and passions — chief among them to employ its potencies and whatever meagre power to widen the horizon of political possibilities — to crack history open and yes, the nightmare is a possibility and yes, Palestinian resistance is imperfect, but the nightmare is not the only thing one on offer…What this informs us, or tells us, is that many thinkers are capable of a stance that at its heart is anti-intellectual.